TO DRESS LIKE A JEW

Illuminated manuscripts, candlesticks, even synagogue architecture are all, to some extent, anonymous forms of cultural expression: unless someone has entered the Jew's home, or accompanied the Jew to their place of worship, these forms of material culture we have seen so far do not label individual Jews, on the street, as "Jews" (and, if someone is inside a Jew's house, or accompanying them to a worship service at a synagogue, the Jewish cat is likely already out of the bag).

One form of material cultural expression that does overtly identity someone as Jewish is dress: clothing, either in style or in particular accessories, can be perceived as "Jewish" on sight, thus providing a material link between Jewishness and appearance.

Two accessories have been traditional in Jewish dress since the middle ages. One is the tallit, the fringed shawl that fulfills a Torah commandment ("fringe your garments"). The other is the kippah or yarmulke, the skullcap that became traditional (although not commanded in the Torah) in the Middle Ages. Both of these were traditionally worn only by men (although, in recent decades, women of more liberal denominations have taken to wearing them in ritual contexts).

Some Jews wear the fringes and the skullcap all the time. The fringes (called tzitzit) are attached to undershirts or otherwise incorporated into daily dress, like this t-shirt which is designed to go under a military uniform (or, as here, be worn in "casual" mode):

You can see the fringes (four, the traditional number) attached to the ends of this khaki shirt. The fringes are wrapped in a certain traditional manner. This man walking in his garden would be recognizable to passersby as a Jew (or, at the very least, his fringes would make him stand out).

The skullcap has no formal requirements, other than covering the back of one's head. For this reason, it is more amenable to "cultural adaptation" than the fringed shawl, as these "specialty" skullcaps show:

Some Jews have chosen to restrict their wearing of such traditional accessories only to ritual contexts: when they enter a synagogue to pray, they put on a skullcap and a fringed shawl for the duration of their ritual activity.

This transformation of traditional dress into ritual dress opens up new opportunities for some modern Jews to create stylized, "modernized" interpretations of traditional Jewish culture.

Consider this gentleman:

He is wearing what would be considered a "traditional" prayer shawl, for use in a Jewish synagogue. The more delicate embroidery and materials used make it impractical to wear in a daily context, and make it appropriate for "special," ritual occasions (you cannot see the fringes, which are attached in a halakic manner on the corners of the shawl).

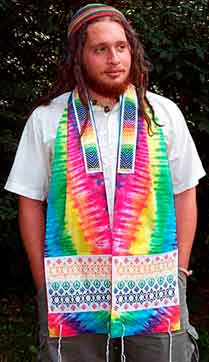

Other people choose to make their ritual garments a matter of personal expression, such as this gentleman:

In direct contrast to modern Jews who restrict their Jewish dress to ritual occasions, more "traditionalist" Jews (who, by definition, will always choose tradition over modernization) have retained a form of archaic dress that immediately marks them off from others. They dress in a manner that is deliberately "un-modern," the way their ancestors dressed in European villages before they were legally emancipated and integrated into modern society. Usually they wear black hats, thick wool suits, and let their beards and sideburns grow out.

That they choose to dress in such a deliberately "un-modern" fashion should not be interpreted as separationism. Often such non-modern, traditionalist Jews are well integrated into society, at the cultural, political, and economic levels, as these "traditionalist" Jews make clear:

Rather their particular mode of dress is designed to mark off their Jewishness, make it obvious to all who see them.

end of slideshow