arabesques: word, art, image

Islamic art is generally what art historians call aniconic: that is, it regularly avoids depictions of humans. Early in Islam, the depiction of human or divine figures was considered dangerously close to idolatry. "Imaging" the divine would be shirk, that is, the "association" of an image with the singularity and transcendence of the divine. Some historians of religion think this might have something to do with the prominence of icons in Byzantine Christianity. Muslims were already suspicious of the Trinity as an example of shirk; the veneration of icons might have seemed equally suspicious for an absolute monotheism.

The absence of figural representation does not, however, mean that there was no artistic creativity marked distinctively by Islamic concerns. In fact, the parallel between Jesus and the Qur'an in Christian and Islamic understanding of how humanity has been reconnected to God might also be paralleled in their respective material cultures. Whereas Christians developed complex artistic representations that evoked Jesus Christ, Muslims elaborated the written form of their own connection to God: the Qur'an.

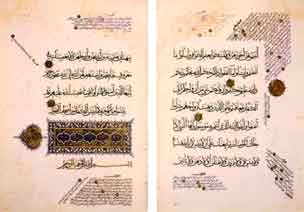

The significance of the Qur'an has always been in its recitation; but as written copies began to circulate, the Arabic letters became a site of artistic creativity (as long as the words themselves were clear to a reader).

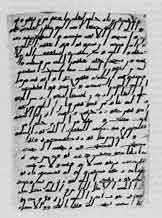

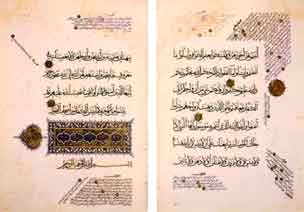

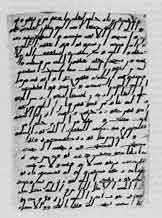

Below are some examples of creative calligraphy (artistic writing) of the Qur'an. The first image is of one of the earliest surviving copies of the Qur'an (from the first century after the hijra), before dazzling illumination became common:

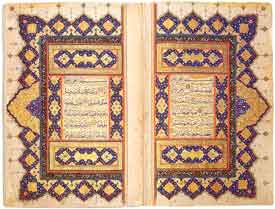

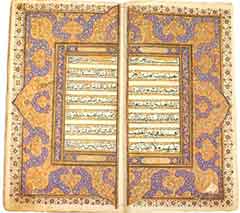

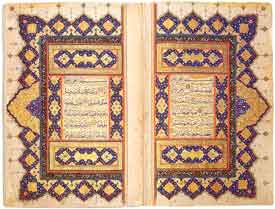

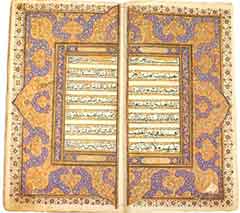

The artistic elaboration of the spirals, curls, and lines of Arabic in these illuminated Qur'ans led to an emphasis in non-figural Islamic art and decor on geometry, and the creative mixture of shape, color, and pattern that became characteristic of Islamic art around the world. The characteristic curled and geometric extension, reminiscent of Arabic letters, became known as the arabesque.

This is a wall from the "Great Mosque" in

Cordoba, Spain, complete with "arabesques." Compare the nonfigural

representation with these examples of classic Qur'anic scripts:

![]()

![]()

It became common for architecture, decoration, and Qur'anic script to evoke and even reproduce one another: Arabic words used as design patterns in architecture, architectural motifs used to illuminate precious copies of the Qur'an. The "word of God," the center of that revelation through Muhammad that is at the core of Islam, could thus truly permeate Islamic life.